Children face multiple threats online – social media create just some of them.

Cyber-bullying, mental health challenges, misinformation, disinformation, online hate, extremism, radicalisation, AI slop, dark patterns, inbuilt features that drive addiction, privacy risks, data misuse, algorithmic manipulation…and this is just the everyday stuff, before we even get to serious criminal activity: online scams, grooming, fraud and the prevalence of violent pornography and CSA material.

All these can be encountered on social media, yes – but they’re also to be found elsewhere on the internet. Sadly, social media is just the tip of the iceberg. This is the main reason a ban for under 16s won’t work – not at least, in terms of doing the job we want it to.

Growing pressure for a ban

Last week Spain joined Australia in introducing a social media ban for the under 16s. Social media is “a failed state“, according to the Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez. The European Union and at least seven other European countries (including France and Denmark) are also considering a social media ban for children. In the US, eight states have bought in either outright bans or parental controls for minors to open accounts. New York City recently passed a bill to introduce mental health safety warnings across social platforms. Recent books like The Anxious Generation and Superbloom and dramas like Adolescence all add to the sense that social media is increasingly toxic.

Here in the UK, the government has announced a three month consultation into children’s social media and smartphone use. It’s true, we already have the Online Safety Act, which became law in 2023. The act requires online platforms to carry out strong age-verification checks and stop harmful content from being accessible to children. It also grants the government and Ofcom, the independent media regulator, authority to fine or even remove platforms that fail to comply with the rules. In theory, this should be enough.

Why a ban is unenforceable

But the success of the Online Safety Act has been patchy. This research (from the European Free Alliance) showed that no currently available age-assurance method adequately meets the combined requirements of privacy, security, inclusivity, and reliability. The report concludes that treating age verification as a foolproof mechanism for child protection is “both illusive and dangerous”. Many organisations, from the Electronic Frontier Foundation to the Center for European Policy Analysis argue a similar point.

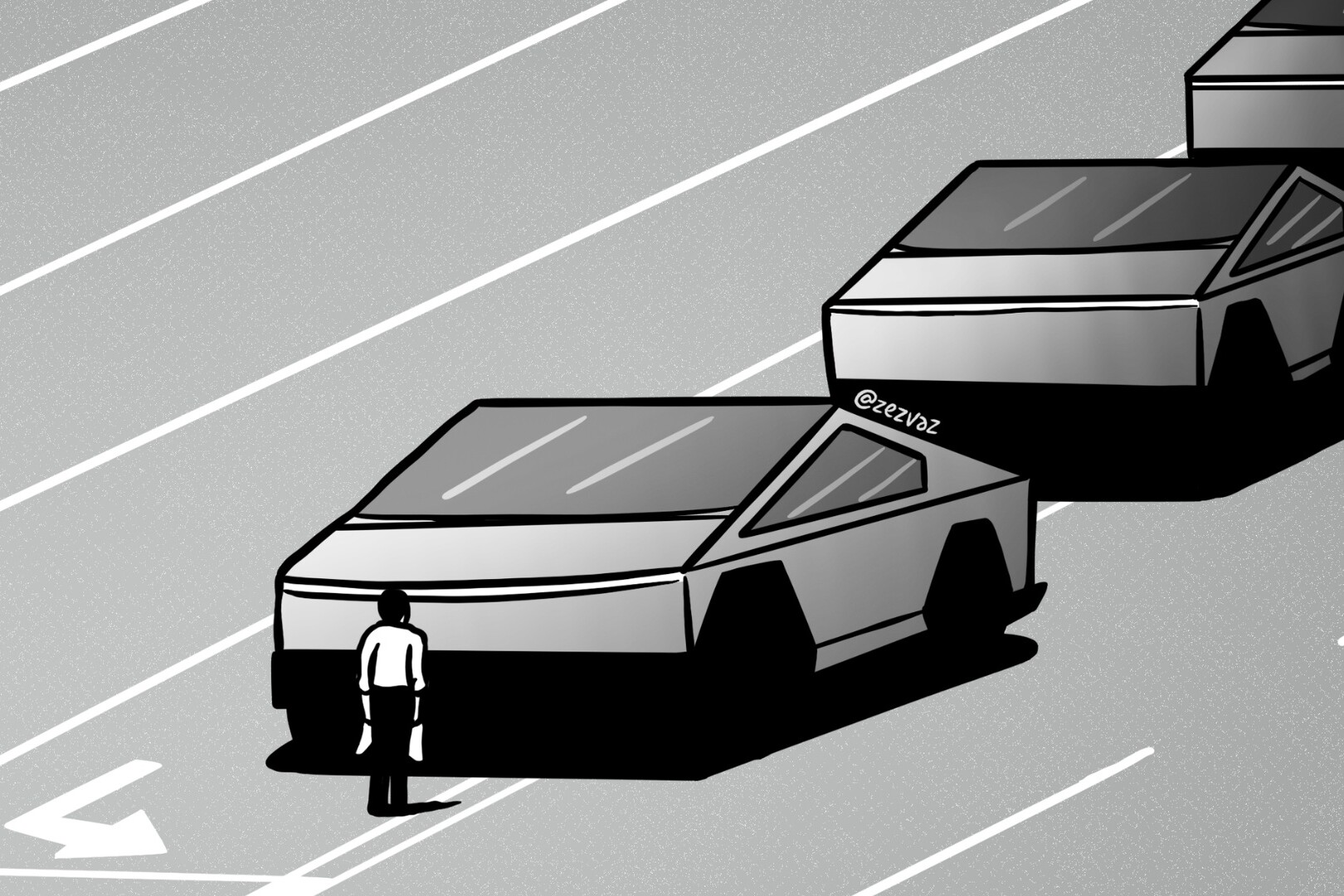

Ian Russell, child safety activist and father of Molly Russell, says a ban is the wrong approach and he is concerned about unintended consequences. One argument he gives is that it’s penalising children for something that the tech companies should be taking responsibility for. The problem isn’t children – or their parents – it’s the business models behind social media platforms. Addictive features and attention-driving algorithms are purposely built into the design of the social media platforms we use. It’s time for the tech companies to take some responsibility, he says, otherwise we (parents) are left to keep on playing Whac-a-mole.

The Guardian recently published a piece asking Australian teenagers how their social media ban was going. Most found it easy to circumvent. Others had simply upped their usage of channels not included in the ban like WhatsApp, Pinterest or Netflix. One said she was accessing far more disturbing content now she had entered a false birthday and was able to use the platforms as an adult. But it was 15 year old Ewan who summed up the mood: “What upsets me most is the waste of resources that has gone into this whole thing”.

Three things we can do

Instead of a social media ban for under 16s, here’s what I recommend:

1. Ban smartphones in schools

Many schools have already banned smartphones successfully – and it’s far easier to enforce than restricting access to social media. At my daughter’s old school, phones must not be seen or used on site. At the John Wallis Academy in Kent, phones are locked in Yondr pouches throughout the day. Fulham Boys School has a total ban and confiscates phones for 6 weeks if a pupil is found using one. Education secretary Bridget Phillipson recently asked schools in England to ban phones, but her request is not backed up by legislation, and rules vary across the UK.

2. Properly enforce existing laws

Under the UK’s Online Safety Act, personalised services—such as social media, games, and AI chatbots—should not be accessible to children under the age of 13, while certain types of content should be restricted for under-18s. But nothing much seems to be improving. According to many, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is failing in its duty to carry out enforcement activity. For example, despite both the ICO and Ofcom opening inquiries into Grok AI’s publication of at least 3m sexualised images of women and girls, it seems nobody is able to stop Grok’s owner, Elon Musk, doing what he wants. We must keep up the pressure on tech giants, and find ways of forcing them to comply.

3. Develop our own sovereign technologies

The UK’s most powerful supercomputer has just received a £35m upgrade from government to enhance its AI capabilities. This computer is focused on public projects such as reducing NHS waiting lists and addressing climate change. We need more such homegrown investment like this. Unfortunately the business models of companies like Meta and Google (owners of Instagram/ Facebook and YouTube respectively), focus on selling user data to advertisers. This is considered by many to work actively against the social good. Meanwhile Elon Musk (owner of X, formerly Twitter) appears to be using his platform to promote hate speech, misogyny and a white supremacist ideology. The tide is beginning to turn as people become increasingly aware of these agendas and actively seek non-US based alternatives.

What do teens and children think?

I asked my 19 year old about her experience of social media. She says all her favourite influencers are recommending ways to go offline. For her and her peer group, nostalgia is all the rage – anything retro and pre-digital is in demand: vinyl, cassette tapes, phone-free socialising, app-free dating, analogue bags, screen-free cafes and knitting. The new book, Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement, published by the Friends of Attention (a group of artists, activists and academics), seems to capture the vibe: there’s definitely a collective resistance going on.

Meanwhile, observations from the other end of the age scale are more unsettling. Young children – in developed countries in particular – are growing up in a world saturated in digital technology. A recent UK study found that two-year-olds in England watch television, videos or other digital content for an average of two hours each day. In a new report on school readiness, more than half of teachers surveyed said that too much screen time was impacting on children’s behaviour. They cited lack of eye contact, attempts to scroll down on books and a desire to recreate digital devices during any art activity. The overall concern was we’re losing a big part of being human.

Despite these issues, it’s clear that many children benefit from being online in social and cultural contexts. Some experts are concerned that banning social media will cut children off from news. In Australia, disabled children and their parents have been arguing against the national ban, saying that social media provides young people who’d otherwise be isolated with vital support networks. Similarly, LGBQTi advocates have argued that social media provides inclusion and belonging for children who maybe don’t see themselves represented in their immediate local community.

Same as it ever was

Any new technology always brings its own moral panic. We’ve seen this in the past with electricity, television and computer games. As academic danah boyd argues, it’s easy to get carried away when talking about online harms. We love to blame technology for societal harms, says boyd, but to raise children to cope as adults in our flawed and complex world, isn’t it better to “teach them how to cross the digital street safely”?

In fact, there is still relatively scant hard evidence that social media use alone is what causes problems. Zoe Kleinman. the BBC’s technology editor has found that negative research is often flawed. One issue is that we rely too much on self-reporting. Another is that it’s impossible to isolate social media use from other factors such as poverty or peer pressure. Lauren Greenfield’s impressive documentary, Social Studies, tracks a group of Los Angeles’ high schoolers over a year of their lives and does a wonderful job at exposing the myriad of influences (good, bad and ugly) that average teenagers are exposed to.

Pay attention – but where it matters

Besides, if we take away social media, what are the alternatives? Do we want under-16s to spend more time on Fortnite, or hanging out alone with ChatGPT? As children’s rights charity, 5Rights has said, a social media ban might simply “push children toward other unregulated but equally problematic services such as gaming, AI chatbots or even EdTech platforms”.

For example, generative AI throws up as many – if not more – moral dilemmas than social media. Last year, a team of Microsoft researchers found that use of generative AI has a negative impact on our ability to think critically. The campaigning organisation, We and AI has just published an updated paper, A broad taxonomy of AI chatbot harms – with risks including emotional manipulation, dependency and addiction. In fact, the choice we have is not between ethical and unethical AI, says designer Christina Wodtke, it’s simply a matter of choosing the least evil.

Ben Collins, CEO of The Onion, has a term to describe the growing industry of data extraction, attention-sapping algorithms, alt-right memes and cryptocurrencies. As he put it when interviewed by Kara Swisher on her podcast last week: “We need to choose between real money, the real economy and human connection and….whatever the fuck this other thing is”.

A social media ban is a distraction. We need to pay attention where it matters. Let’s get on with the real work – of holding big tech to account. There’s nothing like consumer pressure to kick the techlords where it hurts. And we can only do that through continuing to keep the pressure on and demanding change. By banning smartphones, properly enforcing existing laws and lessening our dependence on their services – that’s how future generations will benefit.

Photo: Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash

Jemima Gibbons

Ethnography, user research and digital strategy for purpose-led organisations. Author of Monkeys with Typewriters, featured by BBC Radio 5 and the London Evening Standard.

Related Posts

24 February 2025

Meta, TikTok, censorship and East versus West

16 November 2024

Innovation trumps responsibility – for now

29 July 2022